©Ukrainian Team/American Alpine Journal

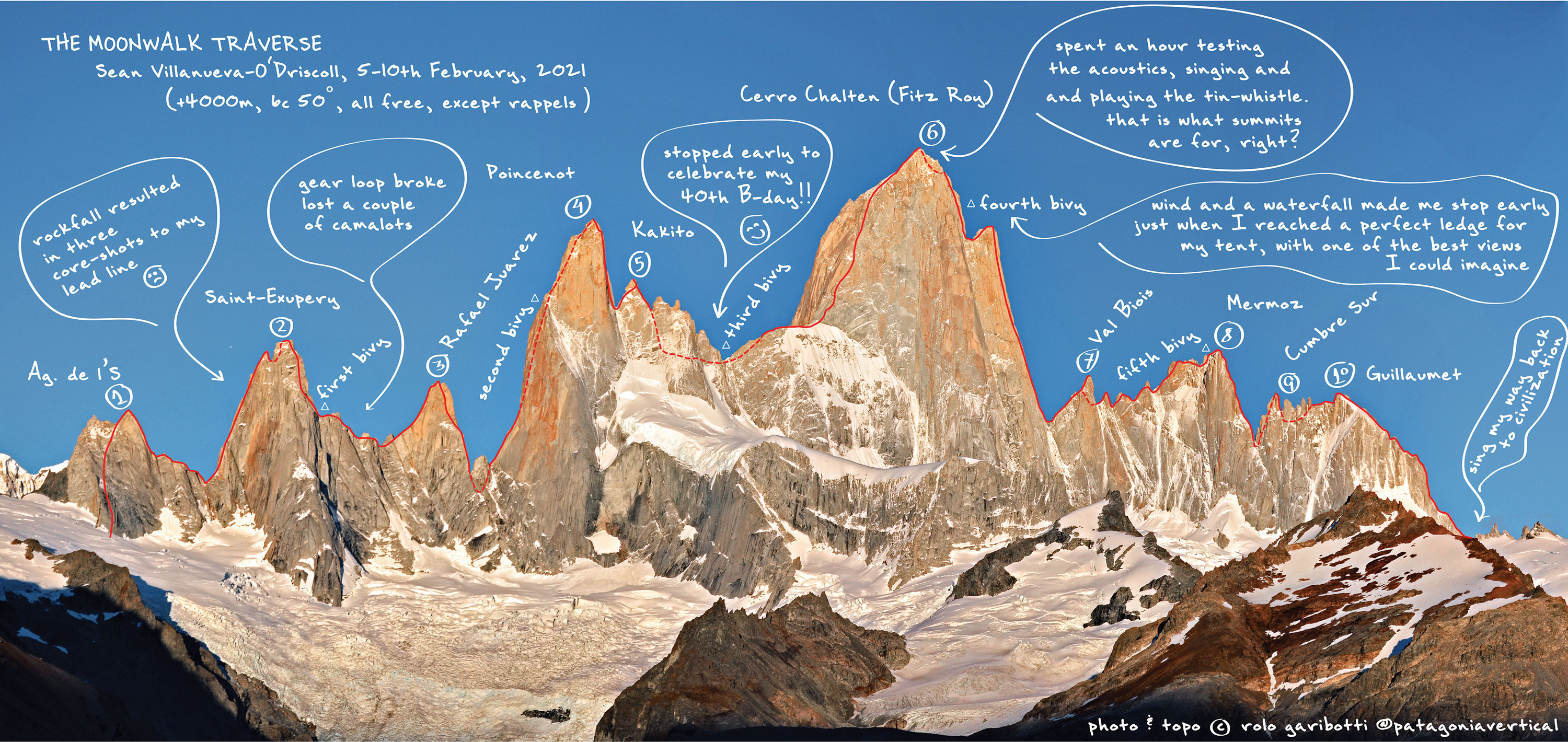

The first ascent of the southeast ridge of Annapurna III (7,555m), Annapurna Himal, via the route Patience (2,950m, 6a A3 M6 80° ice and 90° snow), by Nikita Balabanov, Mikail Fomin, and Viacheslav Polezhaiko (Ukraine). Sixteen days (October 22 – November 6) to the summit from base camp. The three then descended new ground on the west face for a further three days.

The long-awaited first ascent of the southeast ridge of Annapurna III (7,555m) has widely been acclaimed as one of the greatest achievements in Himalayan alpinism in the last few years. Nikita Balabanov, Mikail Fomin, and Viacheslav Polezhaiko (Ukraine) spent 19 days on the mountain, succeeding where many other previous attempts, dating back to 1981 and including their own in 2019, had failed. The route is tactically complicated, extremely committing, and can likely only be achieved when the team has excellent skills, high levels of endurance, and judgement. It also lies in a sector of the country that notably receives worse weather than most of the Nepal Himalaya.

The three Ukrainians acclimatized by summiting a mountain of equal height, the adjacent 7,525m Annapurna IV. They more or less followed a line that had been climbed previously to the northwest ridge but not completed to the summit.

Well over a week later, with their sacs weighing 22-24kg, they crossed the bergschrund below the southeast ridge at 4,600m. They were carrying 12 days food and fuel. Despite an excellent forecast, the weather was poor throughout their ascent. However, conditions on the mountain were much drier than their previous attempt, making the climbing harder and slower. At 6,250m they met the technical rock crux; a steep crumbling chimney, climbed in crampons. At around 6,500m they reached the 1981 high point (equalled but not surpassed by several subsequent parties), where a ca 70m, unprotected, knife-edge snow ridge is interrupted by a very sharp drop. This section – the psychological crux - succumbed to prolonged and creative shovelling. At 7,100m the southeast ridge merges with the south ridge and from there the terrain to the summit is straightforward. Bitter cold and high winds made for a slow ascent and another bivouac at 7,400m.

From the summit, unwilling to descend the route due to its obvious danger, and unable to continue down the east ridge due to the powerful headwind, they opted for the unknown west face. This proved yet another ordeal, but eventually they reached the East Annapurna Glacier.

While such an ascent should clearly be awarded, certain aspects do not comply with the Piolets d’Or Charter.

Piolets d’Or Charter and helicopter use - ethical and environmental considerations

The southeast side of Annapurna III rises from the cirque at the head of the Seti Khola. Accessing this cirque was always considered very difficult and dangerous, traversing steep, unstable

ground above the Seti Khola Gorge. However, several landslide incidents resulted in expeditions in 2007 and 2010 failing to reach the mountain because team members or the porters themselves declared the terrain too dangerous. Since that time four expeditions, including the Ukrainians in 2019 and 2021, have used a helicopter to transport themselves and all equipment into the cirque.

After descending the far side of the mountain, the three Ukrainians were flown out by helicopter from 5,000m, low on the East Annapurna Glacier (they had asked for a pick-up at 4,500m). Shortly after, one member was flown back to the cirque to collect base camp. All were in Kathmandu the same day.

The purpose of the Piolets d’Or is not only to recognise the most significant ascents of the previous year, but also to use these ascents to promote distinct ethical messages regarding our practices as alpinists, in line with the UNESCO classification of Alpinism as an intangible cultural heritage.

The Charter states that “style and means of ascent take precedence over reaching the objective itself”. Access is not, as such, part of an ascent but is obviously becoming an important ethical and environmental issue. The spirit of the Piolets d'Or suggests that when a place cannot be reached through regular transport routes, or on the ground “by fair means”, it should be left for future generations.

The Charter also includes the criterion “respect for the environment”. In the last decade or so the usage of helicopters for access in the Himalaya has grown massively, especially in Nepal where helicopter use has been largely unregulated. Hiring a private helicopter to reach the base camps of 8,000m peaks, and to fly from base camp to base camp to make a series of fast ascents, has become very common for those who have the financial resources. This in a country where, traditionally, base camps have been accessed on foot with the help of local porters.

Those who visit the high mountains see, more than most, the huge toll that global warming is extracting on the environment. True, a significant portion of an expedition’s carbon footprint can be attributed to the international flight, but the systematic use of helicopter charter in Nepal, and more generally elsewhere, is becoming highly problematic. It is incumbent on us as mountaineers to act responsibly and limit our impact.

The Piolets d’Or would like to send a clear message that the high mountains and the people who live beneath are being increasingly damaged by climate change. It therefore does not support the use of the helicopter for general access.

The Jury agrees that from a climbing perspective the new route on Annapurna III is one of the major ascents in recent years. However, it also agrees that it does not comply with all aspects of the Charter. After considering both points it has decided it cannot award a Piolet d’Or and has conferred instead a Special Jury Award.